Once upon a time, the tallgrass prairie covered 240 million acres of North America. Today it is one of the most rapidly vanishing habitats in the world. Only one percent of the prairie has survived. Maintaining and restoring the prairies is paramount because of their diverse ecosystems, second only to the rain forest. here-ing is a collaboration with the Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research and The Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas. In the words of the curator Joey Orr, “The project offers an arts and humanities framework to be in conversation with a site of scientific knowledge. The environmentally embedded artwork takes into account human movement on the land within the parameters of a gentle prairie reset. It is a novel approach born of artistic and scientific collaboration that operates beyond the constraints of both disciplines.”

Instructions to find here-ing: Searchable on Google Maps. Suzanne Ecke McColl Nature Reserve (adjacent to Roth Trailhead). From I-40, take East 1600 Road north to the parking lot.

In Honor of the Land

Teaser for an upcoming short documentary on here-ing:

Video by Anna Chiaretta Lavatelli at Solid Pink Productions.

Stone and Finger

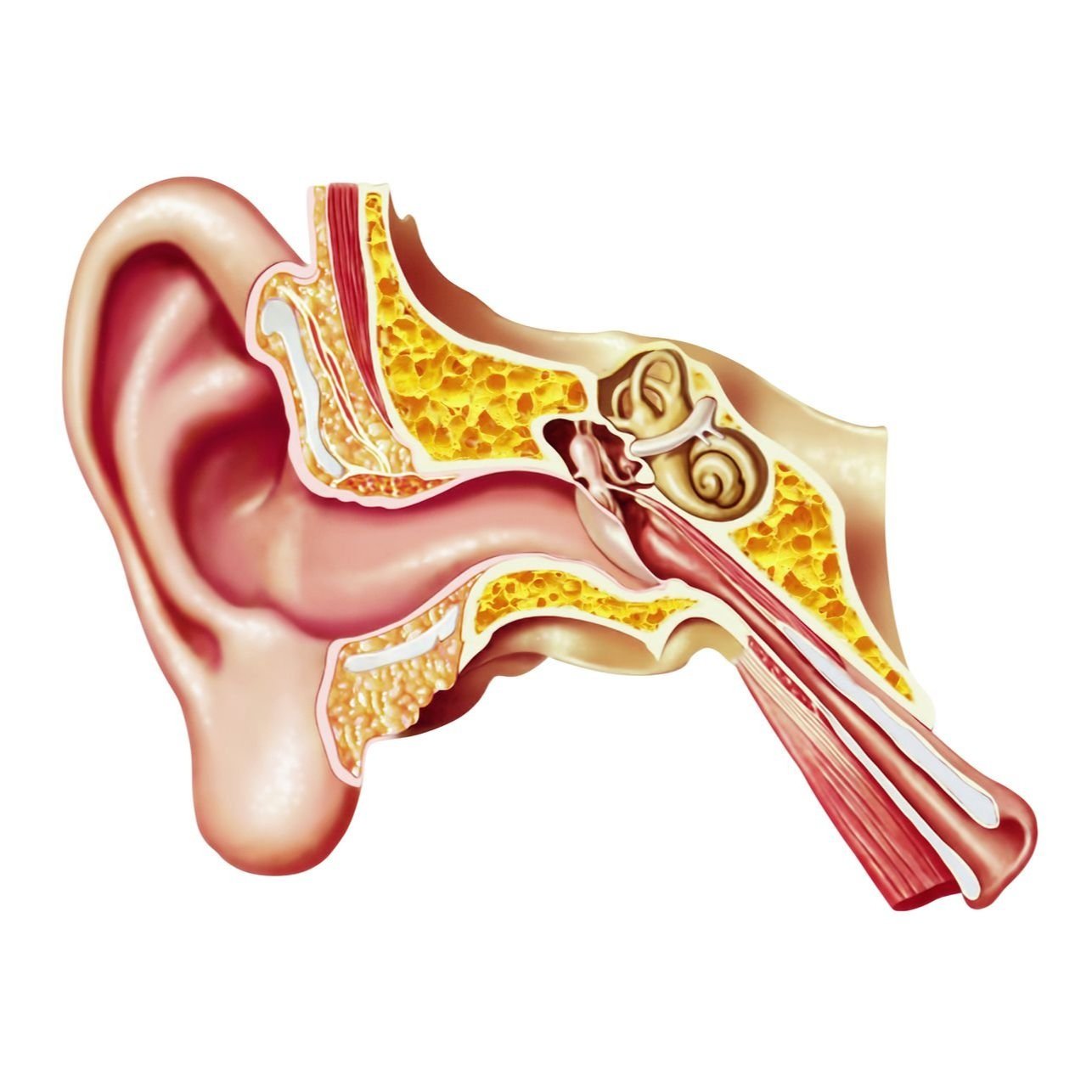

At the start of the path of the anatomy of the human ear lie two large limestone boulders. Carved into the stone is a finger labyrinth which gives you the opportunity to traverse with your finger the path through which you hear, and to have an overview of the path you’re about to walk. Through bodily memory, you can orient yourself in space.

Thank you to Sheena Parsons for preparing the ground, to Keith VanDeRiet for placing the boulders with finesse, and to the three carvers: Karl Ramberg, Matt Bellomy, and Terry Frankenfeld.

The Prescribed Burn

Indigenous wisdom has taught us that we need to periodically perform prescribed burns in order to maintain the prairie. The fire in fact rejuvenates the prairie plants, helping the grassland thrive over their woody competitors that would take over. It also removes dead plant material enabling prairie seeds to more easily find their way down to the soil, and the soil itself is fed nutrients from the fire. Burning helps to encourage biodiversity of the land’s former prairie ecology.

The Ceremony

Antoni selected a diverse group of community representatives to perform the burn. They were accompanied by field station staff to ensure their safety. The ceremony was intended to link each participants’ wish for personal transformation with that of the fire’s power to heal the land. The work provided an opportunity for people to have an embodied connection to this specific piece of land, to become invested in its healing, and to learn from it in a deeply personal way. Our gathering was a place to feel a sense of community. The participants received a couple of emails before the event that explained the reason for the burn and asked them to contemplate something in their lives that they would like to let go of.

As participants arrived they were greeted with handouts that contained character sketches of the three most prominent invasive species in the field. They were asked to choose one invasive plant that matched up with something that had once served them in their lives, but that are now ready to let go of. They were then given a bundle of the dried invasive plants of their choosing.

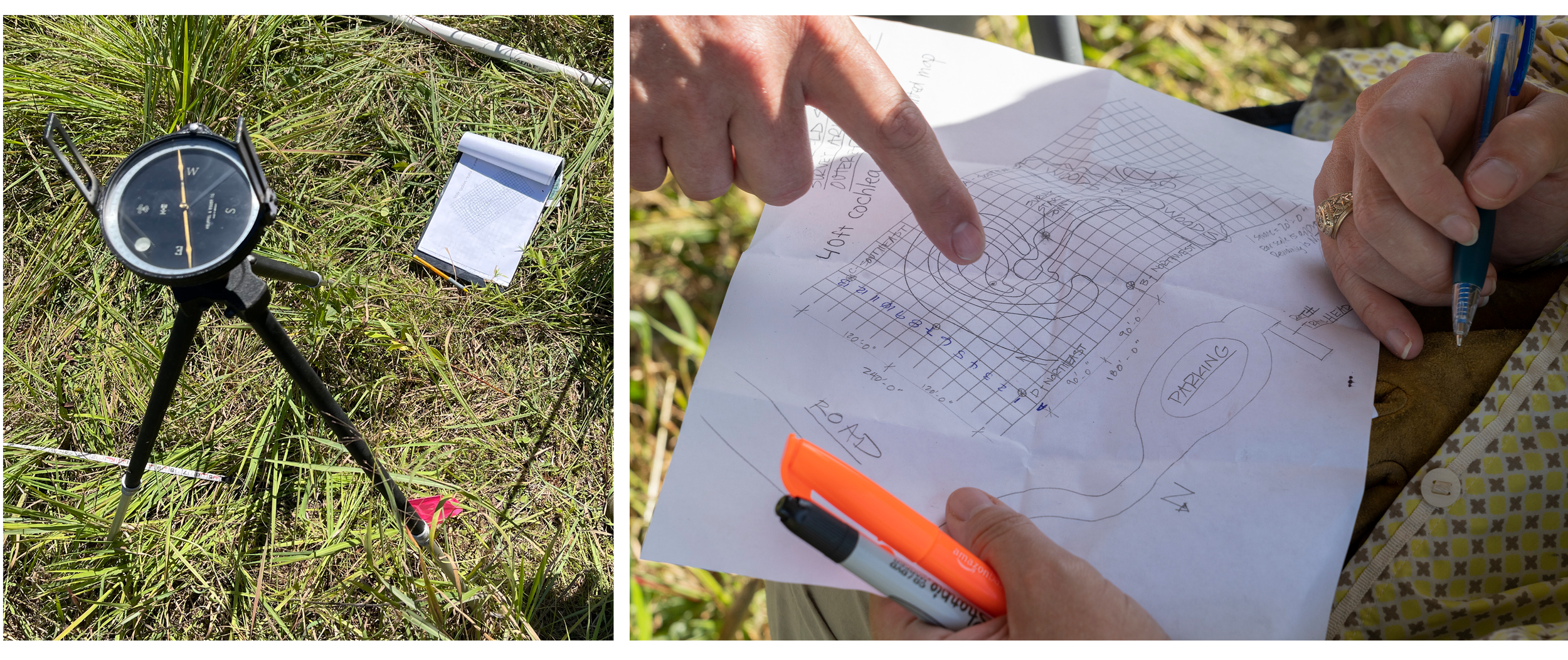

The Grid

Featuring: Keith Van de Riet and his Designbuild class from KU Architecture & Design Department

Under the scorching sun, we established a grid in the land in order to scale up the drawing of the outer ear. With the aid of a transit, an instrument used for land surveying, we laid out 130 posts in a 20 foot grid that stretched 250ft x 130ft.

The next day we used the grid to draw the labyrinth into the field and connect the post with orange marking tape for future walkers to follow. We then removed the grid and began walking. We had over a 100 visitors that offered their step to establish the path. A few days later the Designbuild class returned to walk the ear and experience the fruit of their labor.

Native milkweed plugs have been planted along the edges of the labyrinth footprint to enhance pollinator habitat. KU Field Station staff have lead a series of seed collection events with local volunteers to gather seeds to be used for restoration efforts surrounding the labyrinth site next spring.

The Tours

In October 2022 there was a series of tours led by experts in the field of ecology, embodiment, and human anatomy. The public walked back and forth through the labyrinth, enhancing their relationship to the ecology along the trail, as well as their bodily awareness, both in terms of anatomy and felt sense. We listen with all parts of our bodies in order to learn and to feel interconnected. Through repeated walking, the anatomy of the ear continued to be imprinted on the land. We join our inside to our outside and, in doing so, find belonging.

Getting to know the field

Tour guides:

Jim Bever (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology/Kansas Biological Survey) spoke to us about the resilient microbiome in the prairie.

Jim Bever explained how post agricultural planted prairies, like the field where the outer ear is placed, suffer from lack of biodiversity. Restoration is difficult as we can not just plant prairie plants and expect them to grow without the microbe magic that has been disturbed by farming. Again and again we learn that diversity in all its forms means health.

Photo by Ryan Waggoner, © Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas.

Dianne Durham (KU Medical Center) walked us through the anatomy of the ear and how it functions.

Dianne Durham giving a tour of here-ing.

She taught us about the funneling effect of the outer ear, which allows sound to enter the ear canal and make its way to the cortex; where it is interpreted and identified by the brain. Our two ears create a time lag in hearing, helping us to locate the direction of the sound. Did you know that every human possesses a unique sound signature? Because of variation in form, we all hear differently.

Photo by Ryan Waggoner, © Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas.

Bob Hagen (Environmental Studies) reminded us of how the land came to be.

Bob Hagen giving a tour of “here-ing.”

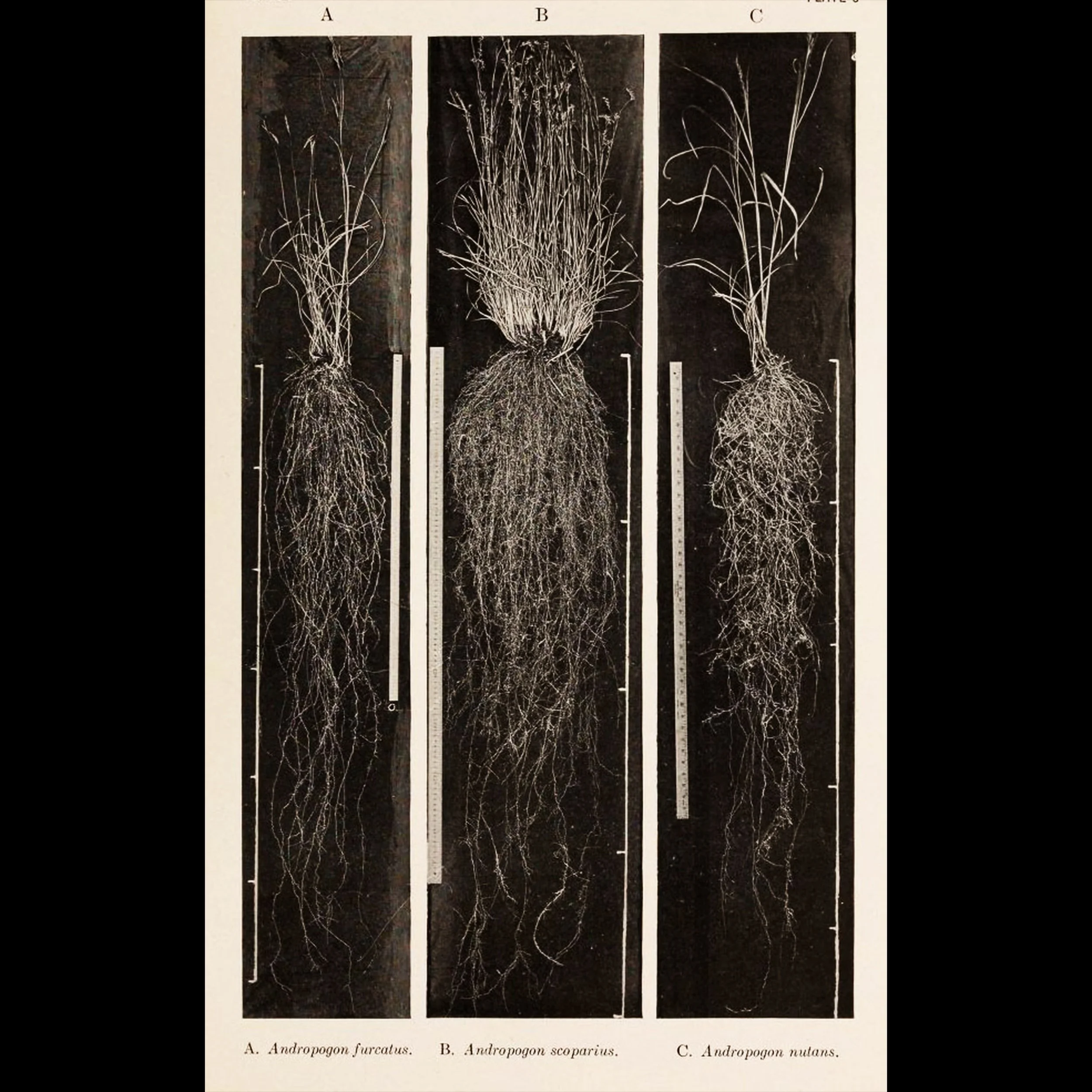

Growing longer than our own body, those prairie roots reach deep underground sipping at water tables and surviving in times of drought. Intense demands for grain encouraged farmers to ravage the flat lands of the prairie, damaging one of the most diverse ecosystems. Plowing for farming destroyed this complex root system, draining the prairie’s natural wealth, years in the making. The dust bowl taught us the hard way that without this intricate, sprawling network holding down the soil, our land turned to dust and the wind carried it away.

Farming the prairie. Courtesy of Center for Great Plains Studies.

“The ecological relation of roots,” published 1919 by John Ernest Weaver, with image assistance from Miss Annie Mogensen and Mrs F.C. Jean.

Postcard depicting The Dust Bowl in Kansas April 14, 1935. Photo courtesy of The Ellinwood Kansas Historical Society.

Photo of Bob Hagen by Ryan Waggoner, © Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas.

Sheena Parsons (Kansas Biological Survey) had us listen to the grasshopper symphony and spoke to us of their contribution to the field.

Sheena Parsons mesmerizing tour participants with the wiles of the chatty grasshopper!

She taught us about the grasshopper symphony in the field. We learned that they make their sound by rubbing their knees together! Voracious consumers, they help decompose plant matter by sending it back to the soil. Who would think that these small, hungry creatures could do as much work as the big bison!

This is a juvenile (Vth instar, the last instar before adulthood, notice how it doesn't have a full wing, just a little wing pad) female Schistocerca lineata, the spotted birdwing grasshopper. It's one of the larger grasshoppers and can fly quite far to evade capture.

A male Syrbula admirabilis. There are a few common names for this one, admirable grasshopper or handsome grasshopper. This one is likely a dominant stridulators that we hear while out in the field.

A male Melanoplus bivattatus, the two-striped grasshopper. This is a mixed feeding grasshopper, so it will eat any type of plant. This species can exist pretty much anywhere but tends to heavily colonize disturbed sites such as this field.

Kelly Kindscher (Environmental Studies, Kansas Biological Survey) shared his wisdom on ethnobotany and medicinal plants.

Kelly Kindscher standing at the entrance of “here-ing” ready to give his tour on medicinal plants.

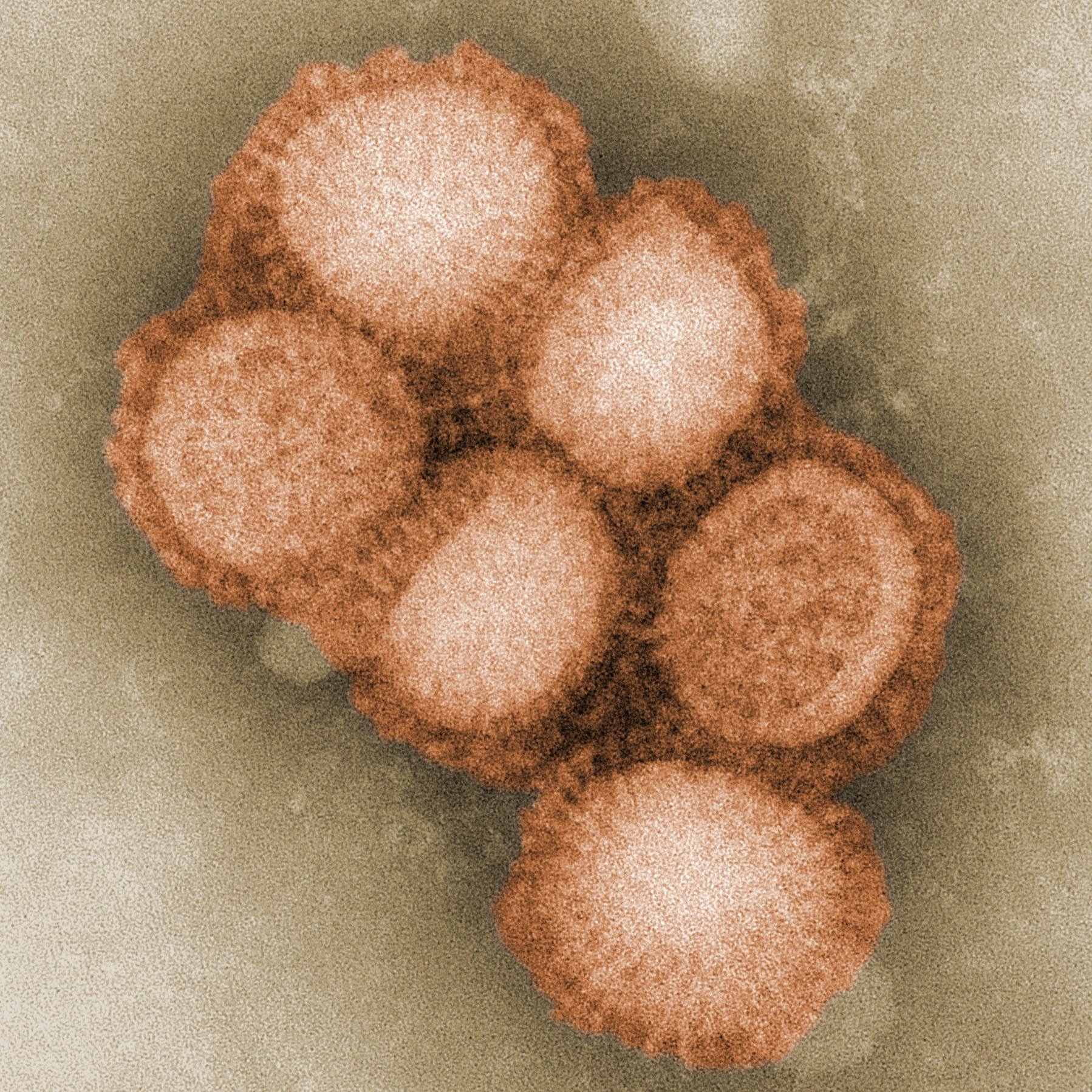

Kelly Kindscher passed on his knowledge about the Tall Boneset (eupatorium altissimum) which grows in the field where “here-ing” exists. A medicinal plant native to Kansas with beneficial qualities like immune stimulation, it was a known remedy for the 1918 flu—not to set your bones but to stop your bones from aching!

A colorized negative of the H1N1 virus, which caused the global influenza epidemic of 1918, the earliest documented case was here in Kansas. WW1 Soldiers suffering from the flu at Fort Riley—just west of “here-ing”—were given Tall Bonset to alleviate their symptoms. Photo by C. S. Goldsmith and A. Balish, CDC.

Photo by Ryan Waggoner, © Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas.

Theo Michaels (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) opened our eyes to the subtle differences in prairie grasses.

Theo Michaels with her bouquet of grass.

She taught us about the subtle differences in grasses. Now as we walk the path of the ear, we feel the Little and Big bluestem, Switchgrass, Sideoats grama and Golden feather as they brush up against our bodies. We listened to the wind rustle their long stems and were reminded of the sound of the waves and how in another time we would be standing on the ocean’s floor.

Sorghastrum nutans, common name Golden feather. Curiously, it is made of glass; not fragile, with the ability to grow up to 8 feet. Its high content of silica gives it structural rigidity.

Panicum virgatum, Switchgrass.

Tour participants in the field.

Photo by Brandon Jessip, © Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas.

Peggy Schultz (Environmental Studies/Kansas Biological Survey) tuned us in to the sounds and colors of the field.

Peggy Schultz speaking about the colors and sounds of the field.

The prairie teaches us to listen with our whole bodies, to merge what we see and hear and feel. Peggy Schultz guided us through an experience of here-ing where the colors and the shapes and the sounds of the land became a full circle of sensation.

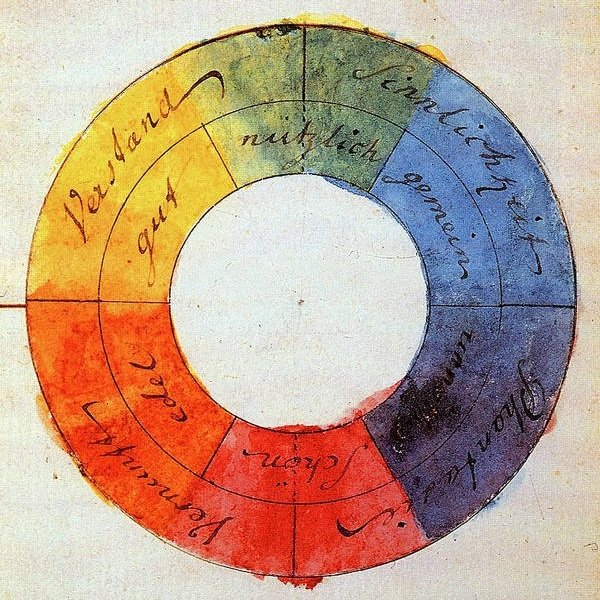

If you look hard enough, the prairie contains the full spectrum. Goldenrod, fall grasses, prescribed burns, sunsets, tall thistle, the sky, and the ground become the color wheel of here-ing.

Goethe believed that the color wheel is arranged according to a natural order where the colors opposite demand and “reciprocally evoke each other.” The prairie demonstrates this reciprocity chromatically and ecologically… all we need to do is listen. Image from Goethe’s “Theory of Colours” (1810).

Photo by Ryan Waggoner, © Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas.

Ben Sikes (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology/Kansas Biological Survey) opened up the worlds under our feet, uncovering the conversation that exists there through the mycelium.

Ben Sikes revealing the secrets under our feet.

Standing at the transition between field and woodland, Ben Sikes tells us about the underworld. The tiny little things that are so hard to see but are essential to the ecosystem.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are the near ubiquitous partners of terrestrial plants, especially prairie plants. The luminous lines are roots, and the delicate tendrils are the hyphae, masters of communication and transporters of nutrients. The tiny spheres are spores, the reproductive structures of the fungus. Many of the trees in here-ing form associations with AMF, but they make spores below ground (no mushrooms) making them harder to know about: an invisible missing piece that slows the transition to old hardwood forests. Image courtesy of Pedro Antunes.

Photo by Brandon Jessip, © Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas.

Helen Alexander (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) took us back in time, explaining the events that transformed the land right up to our present moment.

Helen Alexander began our tour of the path in the field by walking us back in time. 300 million years ago the prairie was an ocean.

Shell form: a memory, a trace, an impression, a mold, a cast. A gift from the venerable Keith Middlemas.

Photo by Ryan Waggoner, © Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas.

If you blur your eyes a bit and watch the grass sway, a golden sea with gentle waves.

The Cultural Burn

Dr. Melinda Adams (San Carlos Apache Tribe), guides us in a cultural burn of the field where the outer ear of here-ing sits. We tended the “good fire” to steward the land and invite the prairie's diversity back. Thank you, Melinda, for bringing back the wisdom and tradition of your people.

Melinda using a white sage bundle, gifted by the Ioway Tribe of Kansas and considered medicine, to ceremoniously start the first fire of the cultural burn.

Photo by Wendy Holman.

Sheena Parsons, Manager of the KU Field Station, collaborates with Dr. Melinda Adams, professor of Indigenous Environmental Science at KU, in their love for fire as medicine to heal the land.

Photo by Suzan Hampton.

The field with the path of the outer ear before burning.

Photo by Dan Hughes.

The fire rejuvenates the prairie plants, helping the grassland thrive. It also removes dead plant material, enabling prairie seeds to more easily find their way down to the soil, and the soil itself is fed nutrients from the fire. Burning helps to encourage biodiversity of the land’s former prairie ecology.

The fire as it moves over the outer ear.

Photo by Dan Hughes.

The charred field after the burn with the path of the outer ear of here-ing still visible.

Photo by Dan Hughes.

Seedlings in the Field

April 2023

Along the entrance to the outer ear labyrinth, with help from Sheena Parsons, Dr. Kelly Kindscher’s capstone class did the planting of 100 perennial plants native to the Kansas bioregion. These baby seedlings are a continued effort to increase the biodiversity of this overfarmed prairie.

Each seedling is inoculated with a tablespoon of MycoBloom - a beneficial fungi to stimulate root growth. Jerusalem artichoke rhizomes were also transplanted from the KU Medicinal Native Plant Garden down the hill.

We are so thankful to the students for all their hard work: Mary Catherine, Summer Sexton, Fatima Chabuk, Addie Amos, Ayub Ahmed, Alanna Treu. It could not have happened without Courtney Masterson & Native Lands Restoration Collaborative for donating their native perennial seedlings. And thank you to Shaughnessy Construction in Iola, Kansas for loaning us a water tank & truck to keep our seedlings moist until the rain comes down.

Photos by Suzan Hampton.

A Sip of the Land

In gratitude for the tea that we have been serving at our events when visitors come to walk here-ing. It comes from Maggie’s Farm, a stone’s throw from the site where the path is embedded. Sending many thanks to Barbara and David Clark for communing with the land in order to share with us a taste of the prairie.

Barbara and David Clark of Maggie’s Farm.

Imani Aisha Wadud and her daughter Aminah enjoying tea together after a long walk, and Keith Van de Riet, an integral part of the here-ing team, cooling down.

Maeve Hilgers, from Maggie’s Farm, posing with her pollinator mug beside Mountain Mint.

And then there are the native prairie plants that make up the tea. Each one comes with their own stories, medicinal properties, and histories.

Yarrow

Yarrow is said to be the only herb you need. Its many names capture its many uses, each one bringing to light another human–yarrow connection.

Yarrow’s species name Achillea Millefolium comes from its featherlike fronds of ‘a thousand leaves’ and the Greek mythological figure Achilles. “The myth goes that Achilles’ mother, Thetis, made him invulnerable by dipping him in Yarrow laced waters of the River Styx while he was still an infant. The only place he was not protected was where she held his ankles. Achilles continued to use the healing powers of Yarrow to stop the bleeding wounds of his soldiers in battle” (Rachel Budde). The leaves of the Yarrow have antiseptic, styptic, and antimicrobial qualities and can be used for healing cuts and abrasions while also cleansing and protecting the area from further infection. Thus giving the plant names like First-Aid Plant and Bloodwort.

Yarrow’s North American varieties have traditionally been used in many Native American spiritual and medicinal practices. The Ojibwe call it Waabanooganzh, or Plant of Life, and inhale smoke from the leaves to soothe headaches and break fevers, or apply decoctions of the root directly to the skin for its stimulant effect. The Navajo call it a Life Medicine and chew the plant for toothaches and use its infusions for earaches. The Miwok use the plant as an analgesic and head cold remedy. The Zuni people apply a juice made from the blossoms before fire-walking or fire-eating. In her book Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask, Mary Siisip Geniusz writes: “In a case where a person is very worried about evil attacking them, for instance in a Bear Walk or in a haunting situation, dried yarrow is pounded and mixed with sand. The mixture is then poured across doorways and window sills or around the entire foundation of a home or around the entire perimeter of a property. It is said that evil will not cross a line of yarrow.”

Its ability to reduce the flow of blood is perhaps why it is known for creating boundaries and protecting energy and space. The stem and flowers are to be placed over a new marriage bed to help create a bond for a long-lasting relationship, and the Druids used it as a strewing herb where they sprinkled Yarrow in doorways to help protect against the evils. And yet, it also became known as Devil’s Nettle or Devil’s Plaything, and used in divination. In the witch trial of Elspeth Reoch, she is said to have cited Melefou, a name variation of Millefolium, to cure distemper.

Yarrow has entranced humans for centuries. In the Shanidar Cave in Iraq, Yarrow pollen was found in the 60,000-year-old grave of a Neanderthal, residue from a burial or healing ritual. But Yarrow plays an important role in non-human connections too. The perennial plant attracts pollinators and repels some pests. Cavity-nesting birds like the Common Starling, line their nests with Yarrow and this has been proven to prevent parasites from growing. Yarrow is a beneficial member the prairie: it prevents monocultures from forming thereby minimizing mineral deficiencies in grazing animals, it is drought resistant, and its deep roots help reduce soil erosion.

Mountain Mint

*Do not consume if pregnant or trying to become pregnant*

Mountain Mint is said to have the power to bring you back from the dead. In fact Indigenous medicinal practice, the fresh flowers would be crushed and stuffed up the nose of a person near to death and the flowers would revive them.

Mountain Mint can be brewed into a tea with a lengthy list of analgesic, antiseptic, diaphoretic, carminative, emmenagogue, and tonic properties. Its healing abilities are far reaching and include the treatment of menstrual disorders, indigestion, mouth sores and gum disease, colic, coughs, colds, chills and fevers. Decoctions can be poured over festering wounds. And the foliage contains pulegone, an aromatic oil effective at repelling mosquitoes when rubbed on the skin.

Mountain Mint’s power to heal lends itself to the land as much as to our bodies. Native to North America, it grows in clusters from rhizomes (horizontal underground stems) giving it the ability to spread compactly. This is demonstrated in its genus name of Pycnanthemum which combines the words Pyknos, meaning dense, and Anthos, meaning flower. This characteristic has led it to be intentionally planted to reduce the spread of invasive species. While it is ‘weed-suppressing’ it is also ‘insect-attracting.’ It attracts pollinators like butterflies, bees, wasps, moths, and even important predator and parasitoid insects that prey upon pest insects.

Despite its name, this mint does not grow in mountainous regions but rather in open fields and at the forest’s edge (ecotones), zones found here in Lawrence where it heals both us and the prairie.

Anise Hyssop

Native to North America, Anise Hyssop grows in prairies, its purple flowers intriguing pollinators and people alike. Similar to the rest of the mint family, Anise Hyssop attracts honey bees and many native bees like bumble bees, mining bees, leaf cutter bees, and sweat bees. Butterflies, moths, and hummingbirds all gather to its fuzzy spikes seeking nectar, and goldfinches come later to eat the seeds.

Anise Hyssop has had a long history in Native American herbal medicine, it is used as an infusion in tea, which the Cheyenne drank to relieve a ‘dispirited heart.’ Known as Kuntze to the Chippewa, the roots are used to ease coughs, bronchial congestion, and respiratory ailments. The leaves are included in cold remedies for its expectorant and cough suppressant properties. Anise Hyssop is also used internally to treat fevers and maintain digestive health. The leaves are cardiac and said to be able to strengthen the heart. Externally, as a wash, it can treat fungal conditions and reduce itching from poison ivy. Its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties lend it to being applied directly to the skin as a salve or poultice to soothe wounds, burns, and skin viruses. Burned for its aroma, its uplifting fragrance has been cited to treat melancholy and depression.

Anise Hyssop has become synonymous with its cousin Hyssop, a plant of Biblical mention and sacred in Judaism. Hyssop is an important plant in rituals for protection. The word ‘hyssop’ is of Semitic origin and describes aromatic herbs used medicinally and in purification rites and ceremonial sprinkling. A fresh cut branch of Hyssop was used as an aspergillum in early Catholic ceremonies to sprinkle holy water as a blessing or for healing. Although they are a distinct species, Anise Hyssop is equally a symbol for spiritual safeguarding. The Cree include Anise Hyssop flowers in their medicine bundles, and the plant is often burned as an incense for protection.

Anise Hyssop stands tall helping us to take care of our bodies with its gifts, its taproots grow down into the prairie soil reminding us to keep ourselves safe, pollinators swarm to its flowers nudging us to embrace interspecies kinship.

Wild Bergamot

*Do not consume if pregnant or trying to become pregnant*

In American lore, Wild Bergamot tea has become symbolic of revolutions. Known as Oswego tea after the Native American people who drank an infusion made from the leaves and flowers, it became co-opted by the American colonists of the Boston Tea Party who drank Wild Bergamot tea during their boycott of the highly taxed British tea.

But Wild Bergamot has had a longer history than being a tea of protest. The plant has been important in Native American medicinal practices for a long time and is used for its antiseptic, anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, carminative, diaphoretic, diuretic and stimulant abilities. It can be used internally, as a tea, to treat colds, headaches, and gastric disorders, and to aid fevers, nausea, and insomnia. Externally, it can be used as a poultice or decoction for burns, wounds, infections, and rheumatic pain. Wild Bergamot can even be inhaled through steam to help sore throats and bronchial inflammation or used as a perspiration inducer in sweat lodge ceremonies. It is a natural pain reliever for cramps and menstruation as it is an emmenogogue, meaning it can be used to bring on delayed menses and to move circulation in the reproductive tract.

The leaves, stems, and flowers of the native Wild Bergamot are all edible and can be used in salads and medicinal teas alike. It is in the mint family, which can be detected by the plant family trait of square-shaped stems. Its fragrance is said to be Oregano-like or even akin to the citrus Bergamot that it is often confused with.

Its wild variety, Monarda fistulosa, grows in open meadows, prairies, and grasslands, and along roads, forests, and disturbed land. Its cultivated form is more commonly known as Bee Balm and thrives in various soil types and can withstand drought. The plant is an important asset to gardens and fields alike as its long flowering stage provides nectar for hummingbirds, wasps, and bees. Wild Bergamot is a source of nectar for the endangered monarch butterflies who migrate through Kansas, as well as a host plant for the sphinx moth, an important pollinator of prairies like these.

In Culturally Important Plants of the Lakota, Linda S. Black Elk writes of Wild Bergamot (or heȟáka tȟapȟéžuta) as being a favored plant among love healers, who are said to receive their power from the elk, an animal symbolic of love and passion. Black Elk states that the “name ‘hehaka tapejuta’ or ‘elk medicine’ refers to this plant's use as a love charm.” Wild Bergamot solidifies its role in the prairie as both love charm and pain reliever, as host plant and as refreshing tea.

In Honor of the Land: an immersive experience at the KU Field Station with Janine Antoni

In October 2023, an immersive event was held to embolden an empathetic experience of here-ing. The prairie holding the work was choreographed to surprise and encourage meditation in the visiting participants. Visitors were invited to walk the path of the anatomy of the human ear and as they returned to their body, they became intimately related to the land.

The event began as Barbara Clark and Maeve Hilger from Maggie’s Farm served tea brewed from native prairie plants. The participants sipped the prairie and learned of the rich histories, myths, and healing powers of the plants they drank. They then wandered over to the finger labyrinth to run their fingers along the grooves in the limestone as Karl Ramberg spoke about the process of carving it.

Shifting from stone to land, everyone gathered together in a circle to listen to Melinda Adams as she spoke about the history of the Indigenous practice of a cultural burn and her work as a Good Fire Advocate. The springtime fire burned in memory and the autumn prairie plants, rejuvenated, shaped the path the participants were about to walk.

Carried across the waves of prairie grasses, came the voice of storyteller Tweesna Rose Mills of the Shoshone-Yakama-Umatilla Nations. In the circle, she sang the traditional Indigenous “Tobacco Song,” a woman’s sweat lodge song from the Kickapoo People of Kansas. Passed down through generations, “Julia Green taught this song to [Tweesna’s] aunt Suzette Mills to pass on and to keep alive in the sweat lodge in the 1970’s. Julia Green’s son, Calvin Masqua, a Vietnam Veteran of the Prairie Band Potawatomi, and Kickapoo Tribe of Kansas bequeathed the words of the Kickapoo Tobacco Song: “Spirit of Tobacco, Father of God, show me the way.” Tweesna is keeping the song alive.

Tweesna then wound her way through the labyrinth singing to the prairie her original work “Coming home” or “Estoy llegando a Casa” an Ocean Song she made for the people of Las Terrazas, Cuba. Tweesna says it’s “a song about longing for home, to always remember home is where your heart is, and to take your Lands and Waters with you wherever you are.” The song traveled through the ear of here-ing and into the participants' ears, and they carried it with them as they started on toward the path.

At the entrance, Janine Antoni offered embodiment prompts for people to meditate on as they walked. Listening with their bodies, the participants followed the event, and the event followed the path of the ear. Outer, middle, and inner. Deeper into the body and deeper into the land.

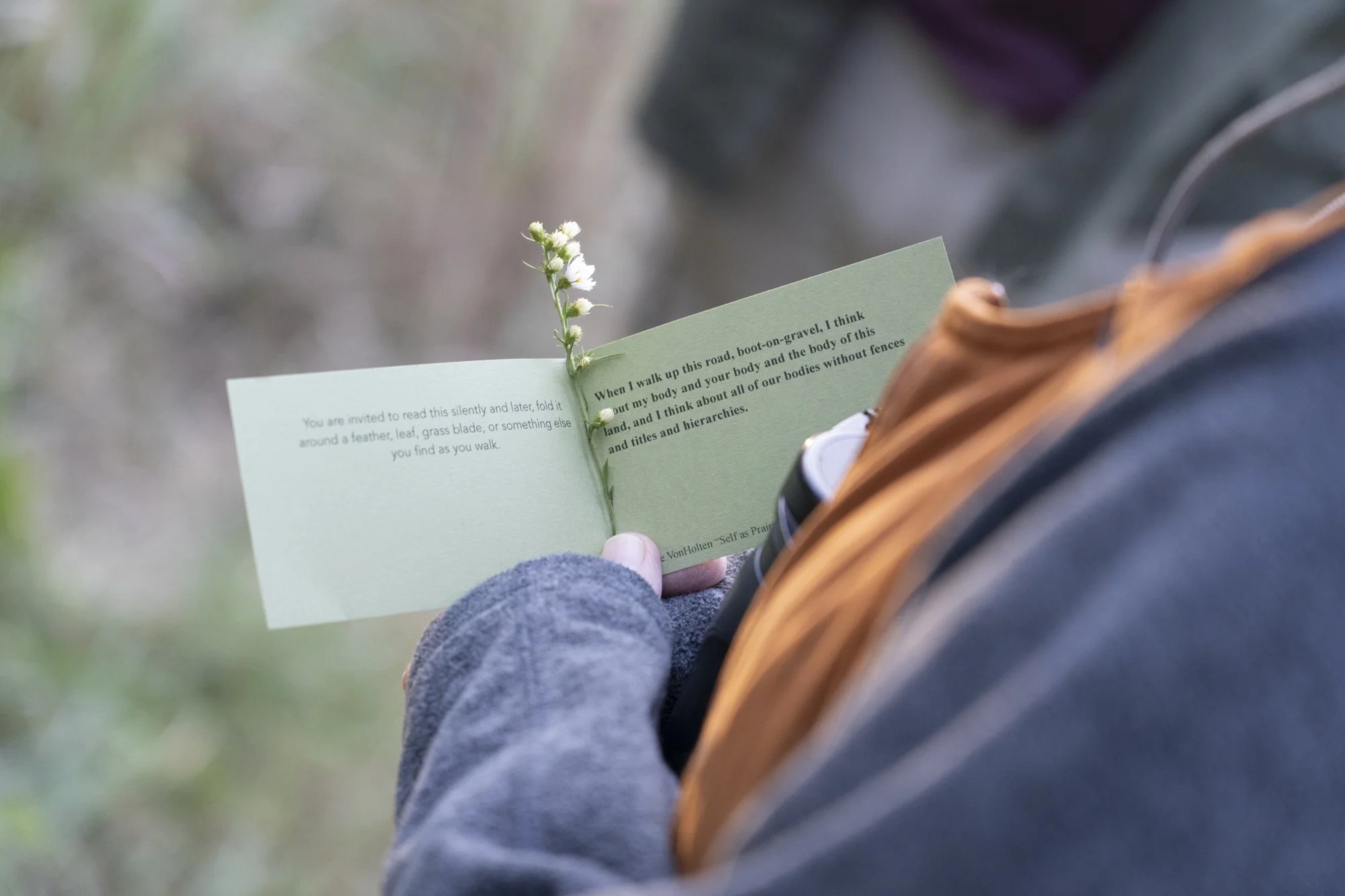

At different points along the path the refrain “Here’s a line to walk with” could be heard. Volunteers and contributors would whisper these words as they presented each participant with a card folded to fit into a pants pocket. Each card contained a fragment from a poem and a corresponding instruction. Prepared by the writer Lori Brack, the selection of poems captured the connection between the prairie and the body, and the instructions offered a deeper experience of both. “You are invited to whisper these words to a tree,” read one. “You are invited to take this home, tear it up, and hide the pieces” read another.

Stationed between the edge of the woods and the middle field, ecologists Sheena Parsons, Ben Sikes and Nathaniel Weickert stood at a transition point: a transition between two landscapes and a transition towards a healthier grassland. The ecologists spoke about the land stewardship efforts being made and the work being done to mitigate invasive species.

Listening to the sounds of the prairie, the participants came to the second bridge leading into the far field. There, they met otolaryngologist Hinrich Staecker, MD, PhD and Suzan Hampton, LEED AP BD+C who explained how we hear. Sound and experience amplified, the relationship between the path and the participants’ own ears reverberated.

At the center of the cochlea, a space that moves in response to incoming vibrations, the participants encountered the drummer Will Meade playing a beat that responded to the rhythm of their steps. The participants' journey through the ear was punctuated by their own footfalls and echoed in the drumming, together they acted out the inner workings of the ear.

Photo by Dan Hughes.

The immersive event has passed but the steps of the people who participated in “In Honor of the Land” live on in here-ing.

Removing Rhizomes

February 2024

On a windy day in February, 11 volunteers joined forces to remove the rhizomes of invasive species from the middle ear. Non-native species management is complicated, and there is no “one-size fits all” approach. This post-agricultural field is completely overrun with Johnsongrass, and we are using a mixed management approach to transition it into supporting a more diverse community of prairie plants. Handpicking the sections of rhizomes helps minimize the number of surviving Johnsongrass plants, preparing the area for the native species that will be sowed in its place. Restoration is a process!

Thank you to all who prepared the land for the native species yet to come.

Photos by Wendy Holman.

Seeding the Prairie

March 2024

Many hands came together at the start of spring to sow seeds in the fields of here-ing.

In the next step to restoring the Johnsongrass infested field, over 30 varieties of native prairie species were planted! The KU Field Station, with the help of volunteers and partners, has been working to steward the land of the middle ear with care and intention.

Photos by Wendy Holman.

Curator Joey Orr and Field Station Manager Sheena Parsons of the “here-ing” team taking care of the land!

Connecting to Place

June 2024

Kansas poet Lori Brack and the Spencer Museum's graduate research fellow, Hayden Nelson led a participatory prairie poetry program at here-ing. The resulting poems are a trace of the event and its participants' responses to walking the path.

The poems 'Full of this magic' and 'Small talk with the natural world' were compiled by Lori Brack using complete lines from each of the participants in the post-walk poetry reflection.

In 'Here-ing', the poem was made by sending everything participants wrote through a William S. Burroughs "cut-up machine." Then, Lori selected and organized lines the machine generated.

Thank you to all of the participants for walking and reflecting.

Photos courtesy of the KU Field Station and Joey Orr

Full of this magic

Grasshopper in sunlight warming up for night:

when the breeze hits the trees

through grasses, glistening leaves as they blow,

light without an obvious source

and what my inner ear will be hear-ing –

snap under prong.

Deer is spooked and glides over grass,

a finger soft breeze, butterfly

floating below the tops of tallgrass.

Deep are the roots beneath my feet.

Prairies full of this magic:

grating calls of frogs warming up for love

Participants walking the path

Small talk with the natural world

Walking in water, walking in grass,

stealth insects hiding –

swish crunch chirp.

To traverse the tall grass

ocean on the prairie,

microbial as a universe,

forced to focus on what I am –

floating below the tops of grass,

circles of sound.

It was worth it.

Reflection through poetry

here-ing

Certain is the prairie,

leaves on leaves,

ocean of moving on.

In light, stealth steps.

Lavender obscures the grass

beneath time walking.

Water, the hot sunlight.

Prairie’s breezy voices,

cool magic of prong

glistening earth’s warming.

Green cedar swish

here traverses sound,

refreshes whirled grasses.

Red the conversation,

natural world chatter.

Participant Writers:

Barbara Axton

Wendy Holman

Hayden Nelson

Joey Orr

Sheena Parsons

Saralyn Reece Hardy

Molly Soukup

Monte Soukup

A History of the Field Station Land

The Spencer Museum’s Graduate Research Fellow Hayden Nelson has been working on an essay researching the history of the land that both here-ing and the Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research Field Station rests on. Hayden has been a key figure in the making of here-ing and his work on the intersection between land change and colonization in the Kansas Prairie provides an enlightening perspective.

In the essay, Hayden describes the ecology of the landscape of here-ing:

“The KU Field Station is located within the prairie-forest ecotone of the central U.S. This climatic transition zone between the eastern deciduous forest and the tallgrass prairie exhibits strong east-west environmental gradients, including rapid decline in precipitation. Because of this ecotonal location, Field Station lands represent a wide variety of ecosystems and are well-suited for studying effects of climate change on a variety of ecological phenomena. Before the settlement by Euro-Americans that began in the mid-19th century, the region was dominated by native prairie, with smaller amounts of native forest and savanna. Actions of these settlers—suppression of fire, cultivation (plowing) of prairie, cutting of forests, introductions of non-native species—greatly altered the landscape. As is typical of the region, the majority of Field Station lands have been altered by human activities. In combination with extant native communities, this provides an unusually rich mosaic of habitats available for study.”

Full essay by Hayden L. Nelson

Hayden L. Nelson is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Kansas specializing in North American environmental and Indigenous history. His work has been published in Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains and the Middle West Review. The American Society for Environmental History, the Newberry Library, and the United States Forest Service have supported his work.

Screening of the Here-ing Documentary

October 2024

People assembled in the field of here-ing. Photo by Ryan Cole Waggoner

In early October, the KU Field Station and the Spencer Museum held a screening of the here-ing documentary within the very landscape it was filmed in. A white projector screen stood on the edge of the tall, swaying prairie grasses of the outer ear of here-ing. In the twilight, people gathered together in the field to watch the film directed by Anna Chiaretta. The documentary, featuring all the remarkable people who helped make the work possible, has found its way back home in the land.

Photo by Wendy Holman

The documentary covers the process of making here-ing from the prescribed burns to the planting of native prairie plant species.

Photo by Wendy Holman